Are Founders With ADHD Built for Entrepreneurship?

Some founders call ADHD an entrepreneurial superpower. But reality is never that simple.

BY PETER KEATING, FREELANCE JOURNALIST@PETERKEATINGNJ

By the time he'd turned 39, in the spring of 2007, Mark Suster was a doubly successful entrepreneur. A Philadelphia native with a University of Chicago MBA, Suster had worked for Accenture around the globe for eight years, and then launched, in 1999, BuildOnline, an Ireland- and U.K.-based software company that enabled collaboration in the construction industry. He steered that business through the dot-com bust and a merger with an American competitor named Citadon, after which he stepped down as CEO.

Then he founded Koral, a maker of content management software, in 2006, and sold that company to Salesforce the following year.

Through it all, Suster was aware that some aspects of his personality had a tendency to make his life more difficult. He couldn't focus on routine tasks; unless he loved a subject, his mind would wander. He couldn't remain at boring meetings. He felt a deep-seated need to pursue only ideas he cared about. He often did multiple things at once without completing them; he'd read five or six books at the same time without finishing any. He was sometimes argumentative, sometimes late for meetings. He didn't see a connection between these idiosyncrasies--or struggles, or problems--but they weighed on him as he tried to decide whether he should stay at Salesforce.

For six months, Suster worked as an increasingly frustrated vice president, trying to figure out how to assimilate as a subordinate. He told colleagues he intended to leave. But before he met with CEO Marc Benioff--the cloud-computing legend already well on his way to being San Francisco's biggest tech employer--Suster told his wife, Tania, that he hadn't fully made up his mind.

"I figured I'd listen, and if I felt enough autonomy, I'd stay," Suster says now. "And if I didn't feel inspired, I would just politely leave."

But his encounter with Benioff didn't leave room for a considered response. "I came into the room that day, and he just started yelling at me," Suster recalls. Benioff famously talks about modeling his company's culture around ohana, a Hawaiian term for extended family. But in this instant, he was a domineering patriarch. "He said, 'I can't believe you're quitting! You're disloyal! I never would have bought your company!' And ... I just walked out."

Suster, with graying hair and a direct gaze, gestures often when he talks. And when he recounts his meeting with Benioff, his hands reflexively rise up, as if pushing back against intellectual restraints. "It wasn't about money, and it wasn't a strategic debate," he says. It also wasn't that he had a personal problem with Benioff; since that day, the two have gotten along fine. "But in that moment, Marc didn't open the door to whether there was room for another entrepreneur at Salesforce, and I realized I couldn't work for somebody else, following directions."

He pauses to consider what he's saying about himself. "I don't think I would have been good in the military," he continues. "The minute I'd start getting instructions that weren't logical, I'd try to argue that we should do something else. That doesn't work well in command-and-control environments. I don't think I'm employable that way in corporate America."

Suster had worked for nearly eight years with the executives at GRP Partners, a Los Angeles venture capital firm that is now called Upfront Ventures. And so, in the wake of his Benioff meeting, he decided to join the firm to help fund passionate entrepreneurs whose products, as he puts it, "have a reason to exist." He became an angel investor, blogger, and all-around key player in the Los Angeles VC scene.

And shortly after Suster started his new gig, his assistant suggested something that, throughout his career, he had failed to recognize: "You have ADD."

"You're crazy," he replied. "I've been successful my whole life." Like many, he'd been led to believe that people with the condition were too distracted, too scattershot, too crazy to succeed.

Then she handed him a book, Delivered From Distraction: Getting the Most Out of Life With Attention Deficit Disorder. At first, it looked to Suster like fluffy pop psychology. "I thought it was hippie-dippy stuff," he says. But in it was a truth that would resonate: "Millions of people, especially adults, have the condition but don't know about it, and therefore get no help."

As Suster dug in, he was shocked at how well the book described him. "I couldn't believe somebody actually understood how my brain worked," he says. "There's a checklist, and it was like an explanation of me"--down to his habit of showing up late to events, an ongoing source of frustration for those around him. "My wife read it and her jaw hit the table."

His boredom. His difficulties finishing tasks. His time-management issues. Suster had a whole array of classic signs of what health care professionals now call ADHD.

HE WAS IN good company. Over the past decade or so, a range of highly successful founders have gone public with their ADHD diagnoses and related their struggles and triumphs. There's Richard Branson, whose Virgin Group is a wide-ranging conglomerate; Ikea founder Ingvar Kamprad; Alan Meckler, whose publishing and trade show ventures have included Internet World; David Neeleman, who founded JetBlue; Paul Orfalea, who launched Kinko's; Tracy Otsuka, who has built a popular podcast and coaching business around the subject of ADHD; and Peter Shankman, who founded a service called HARO that connects journalists and experts. The list goes on.

At the same time, scientists have made major strides in understanding the causes and effects of ADHD. (The American Psychiatric Association refined the name of ADD to ADHD, for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, in 1987. Because Suster does not experience hyperactivity, he sometimes refers to his condition as ADD.)

And during the lockdown stage of the pandemic, when millions of Americans were stuck climbing the walls at home, many began sharing details of their mental health on social media. By the end of 2022, the hashtag #ADHD had more than 18 billion views on TikTok.

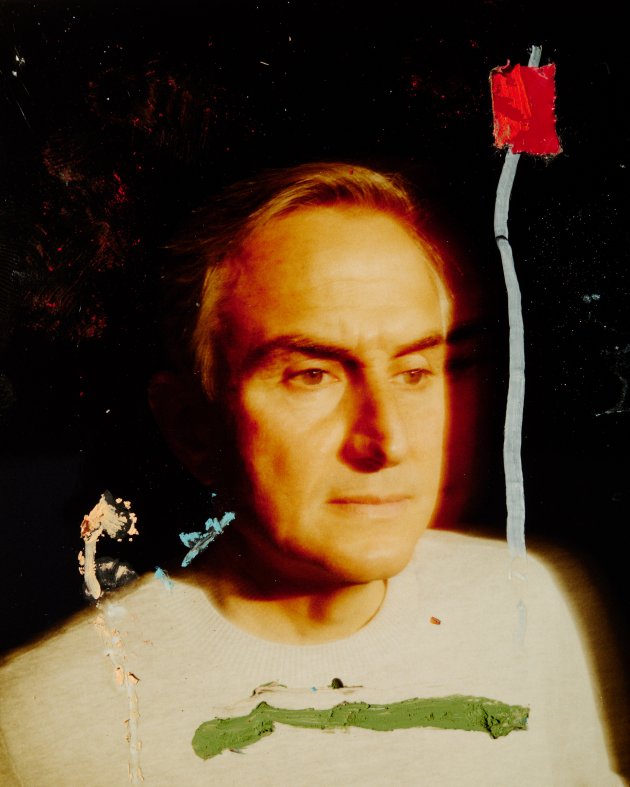

Upfront Ventures' Mark Suster found the upside of his ADHD, the "entrepreneur's superpower."Photography by Brad Torchia

All of which has contributed to what one anthropology study calls an "expanding arena of public intimacy around the experience of disability." Gradually but profoundly, our broader culture is moving toward accepting rather than shunning atypical neurological conditions. Many executives are coming to see ADHD traits such as impulsivity and restlessness as talents rather than disabilities. An entire subindustry of coaching has sprung up, dedicated to helping clients harness their ADHD. (One coach has even said that for entrepreneurs, ADHD "turns chaos into cash!")

But in this moment of correction, a risk exists of turning stigma into a fetish. Less than a decade ago, ADHD was best known as a psychiatric illness alarmingly common among children. Today, hundreds of articles and essays online extol the benefits of ADHD; T-shirts and TED Talks boast titles like "It's an ADHD Thing" and "ADHD as an Entrepreneur's Superpower." And while founders and those they work with increasingly recognize neurodiversity and tap into the special talents it creates, it's equally crucial for them to understand ADHD fully--as a complex condition that can also be an entrepreneur's kryptonite.

THOSE WITH ADHD have tried many ways to describe the reality of it. Edward Hallowell, one of the authors of Delivered From Distraction, calls the ADHD brain "a Ferrari engine ... with bicycle brakes." ADHD coach Brett Thornhill compares it to watching a TV switch channels without holding the remote. Better still, imagine you're in a maze, seeking a prize at its end, like a mouse hunting for cheese. Most people will bump around, eventually progressing through trial and error. But the brains of those with ADHD won't confine themselves to thinking two-dimensionally and making slow but steady progress. They might become obsessed with digging under the maze, or flying over it, or breaking through its walls. They might spend time trying to make a pickaxe or build a helicopter. They might grow so bored that they give up the quest altogether. In any case, the prospect of earning a hunk of cheese fails to engage their brains enough to accomplish arduous tasks.

"If you're super interested in a topic, you can go really deep, so deep that you block out everything else," says Suster. "That's what people don't know about ADHD--you can develop hyperfocus, but only for things that interest you. And in that wind tunnel, you won't want to eat, you don't care about being on time for anything. But when you're not interested, you start to get easily distracted by other things."

If you're wired to apply your own ideas and act without approval, running your own business would seem alluring.

The ADHD mind simply isn't triggered by the rewards that motivate neurotypical brains--which helps explain the link between hyperactivity and inattention, conditions that might otherwise seem like opposites. The link can be explained at least partly by chemistry. In 2009, researchers led by Nora Volkow, the director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, found that people with ADHD have fewer receptors for dopamine in their brains than those without the condition. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter crucial for feeling pleasure and satisfaction.

In other words, for most founders, when an investor hands over a check or an employee says, "You're a great boss," the dopamine level in their brain surges. They feel great and want to repeat the experience. The same goes for everyone else when eating Thanksgiving dinner, or winning a round of trivia, or having sex. But people with ADHD tend to have fewer slots in their brains for dopamine. They generate fewer internal signals of happiness from typically interesting experiences--and fewer still from, say, building a new customer cohort analysis or restructuring an org chart. As a result, they end up less motivated to pursue those things. ADHD entrepreneurs, chasing bigger thrills, may disregard conventional wisdom and take greater risks. They'll act on their impulses. And in the process, they just might discover that shortcut through the maze.

Illustration by Matthieu Bourel

RECORDS OF ADHD-related symptoms have been around as long as human communities have had doctors. In ancient Greece, more than 2,400 years ago, Hippocrates, the father of modern medicine, wrote about patients who had "quickened responses to sensory experience, but also less tenaciousness because the soul moves on quickly to the next impression." Generations of modern scientists first moralized and then medicalized the condition, and derived stimulants to treat it--drugs such as Adderall and Ritalin were designed to help retain dopamine in the brain. But only recently have academics turned their attention to possible links between neurological conditions and entrepreneurship.

In a 2015 report, a team of researchers from European universities looked at more than 10,000 college students and found that those with ADHD-like behavior were significantly more likely to be risk-takers and to want to start their own businesses. Two years later, a Journal of Business Venturing study examined graduates from American business schools and concluded that "certain aspects of ADHD symptoms, such as sensation seeking and lack of premeditation, could lead individuals to be attracted to entrepreneurship and to start their own businesses." A 2018 Academy of Management Perspectives paper by a Syracuse University psychology professor traced connections between ADHD and entrepreneurship to symptoms of hyperactivity (and not to lack of attention).

These and other studies connecting ADHD to entrepreneurship contributed to the ongoing reassessment of how the condition affects working professionals--and helped fuel the hype over ADHD's supposed superpower qualities. To the extent that earlier research had considered employment, it had found those with ADHD tended to have trouble retaining full-time jobs. But those newer findings about ADHD and entrepreneurship make sense. If you're wired to apply your own ideas and act without approval, running your own business would, indeed, seem more alluring than laboring in a traditional workplace. In fact, a 2018 study published in the journal Small Business Economics found that ADHD was prevalent in 29 percent of entrepreneurs, compared with 5 percent of a control group.

Less explored was this: When entrepreneurs with ADHD launch their own businesses, how well do those companies do? In 2021, a report in the same journal considered just that. The authors studied 164 firms in the Netherlands that had launched in the previous 10 years and learned that founders with ADHD symptoms achieved far greater profit margins and customer satisfaction--but only in some cases.

Companies led by founders with ADHD symptoms benefited when those founders cared deeply about launching and growing a business--landing investors, hiring employees, increasing sales. But when founders' ADHD symptoms manifested as a love for inventing--developing new products--their companies performed worse.

The researchers concluded that if founders are passionate about launching and scaling a business, their intense positive emotions can mitigate the negative tendencies of ADHD, such as difficulty sustaining focused attention. But if what they love more than anything is skipping from one idea to the next, that passion can undermine their company's performance--and show up on the balance sheet.

The bottom line: For ADHD entrepreneurs, current passion is no guarantee of future performance. Which means it's severely misleading to call ADHD a blanket superpower. More than anything, using that word to describe ADHD founders is an example of survivorship bias, which occurs when an analyst focuses only on people who have passed some kind of test. Consider, for example, that Major League Baseball players hit about as well, on average, in their late 30s as they do in their late 20s. On the basis of that, you might conclude that age has no effect on batting skill. But that's wrong; hitting declines for almost all players as they age. By looking only at "survivors," you'd be evaluating only those athletes who were great enough when they were young to still be playing when they're older.

Similarly, calling ADHD some kind of superpower might seem reasonable, given the many entrepreneurs with ADHD who have found success. But it discounts the experiences of people who are still figuring out how to manage it, a task many have struggled with their entire lives.

MARK SUSTER GREW up in the 1980s, and he counts himself lucky to have had computers around when they were still a novelty, and to have learned programming from an early age. But that didn't translate to a smooth ride at school. "I was always in trouble," he says. "The rules were so stupid that I had to sit in a class and wait for 90 percent of the people to catch up when I had an answer 30 minutes earlier. I got sent to the office so often that I got to be friends with the staff. I programmed their computers. But I didn't feel good about myself."

Because ADHD is a neurodevelopmental condition, its symptoms typically first appear early in life, though they sometimes recede when children grow up. The latest numbers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, using data from 2016 to 2019, estimate that six million children, or almost 10 percent of Americans aged 3 to 17, have been diagnosed with ADHD. School can be particularly hellish for these kids. For one thing, ADHD often manifests in concert with mental, developmental, or emotional disorders such as anxiety, depression, and autism.

For another, although 77 percent of children with ADHD receive some kind of treatment, determining the optimal mix of behavioral therapy and medication is typically a hit-or-miss, frustrating experience for their families. And forcing a youngster with ADHD to conform to an academic setting is often difficult, even damaging--a foreshadowing of what it's like to make an ADHD adult conform to traditional corporate rules. Unchecked, ADHD can leave those with it chronically disorganized; impatient, frustrated, and angry; and susceptible to sensory overload.

"I had a terrible time in school," says Alan Meckler, the Internet World publishing pioneer. Now 77, Meckler didn't discover he had ADHD and dyslexia until he was decades into his career, and he still vividly recalls his early struggles. "I have an incredible memory, but I have a really hard time concentrating on certain things," he says. "I remember I had to write a paper in sixth grade on Henry VIII. The teacher read the paper, and the class thought it was hilarious. I called him King Herny."

Two years later, a sympathetic mechanical drawing teacher noticed Meckler's difficulty grasping the class concepts. Unable to sustain interest or attention, he was struggling to plug away one line at a time, and largely missing the point. "I don't think you can do this work," said the teacher, who happened to keep reams of old newspapers in the back of the room, some of them decades old. Meckler stepped away from the drawing and found himself content to pore through the old sports sections--going deep on a subject that interested him, like Mickey Mantle's batting averages. "And that's what I did for a semester," he says. "I realized later in life that he knew certain people just had a problem. And I was one of them."

When Raven Baxter, a molecular biologist, was attending elementary school in the '90s, it was ADHD hyperactivity that caused her problems. "I would hyperfocus on my work and get it done early--and for me that meant I needed to go around and do everyone else's homework," she says. "I would get up in the middle of class and stand on my desk. I would jump onto other people's desks. I didn't have bad intentions, I just had ADHD, and I was 6 years old and didn't really know what to do with myself. So I'd be put in time-out and sent home with bad behavior reports."

As for Suster, he performed well in school--but many students with ADHD suffer severe setbacks until they find their groove. Meckler barely broke the minimum possible score on his SATs, but he persevered and ultimately got a PhD in American history. He's now chairman and CEO of 3DR Holdings, which provides news coverage of 3-D printing and quantum computing. Baxter had a GPA of 0.6 her freshman year in college, but earned a doctorate too, in science education. Today, her Dr. Raven the Science Maven business uses lectures, advocacy, music, and fashion to advance science education.

IT'S NOT HARD to see why Suster, Meckler, or Baxter might call ADHD a superpower. All three have managed to leverage productive components of their condition while managing its destructive tendencies.

How can more entrepreneurs do that? And equally important: How can one best manage employees with the condition? Synthesizing the advice of founders, the answer seems to come in three parts. All of them start with turning the phrase living intentionally into a kind of mantra. Because without sustained management, ADHD can drive those with it in multiple directions, with no regard for intent or results, leaving the flares of creativity to peter out like spark showers.

First, ADHD founders urge those with the condition to manage their daily tasks carefully to keep themselves productive, rather than overlooking details in lieu of the big picture. It's also important to consider where a person has had issues in the past, and work to forestall those issues, no matter how silly the fix might seem. If an employee gets caught up reading emails for hours, an egg timer on their desk might help. If they always feel the need to argue, a simple reminder to take a few breaths before replying to others can do the trick.

Second, those who have harnessed their ADHD advocate forming teams of people whose skills complement one another's, to balance exaggerated traits in the ADHD teammates. A spouse, a business partner, or an assistant with a passion for operations matches well with someone who has CEO vision. An ADHD coach can also help. Many entrepreneurs with ADHD have segued into businesses that allow them to share their experiences and help others stay directed. "ADHD entrepreneurs tend to be good at a lot of things," says Tracy Otsuka, who in addition to her coaching business hosts the podcast ADHD for Smart Ass Women. "But just because you're good at it, it doesn't mean you should do it."

Finally, ADHD high-achievers say it's important to create workplaces and schedules that don't force people grappling with the condition to adhere to confining routines every hour of every day. That could mean more remote work. "I'm so much more productive when I can get up and do 50 cartwheels," says Baxter. "Or not having to worry about being late because I lost my freaking car keys for the 15th time this month. During the pandemic, when so many of us were taken out of our traditional workspaces, that flexibility meant everything to people with ADHD."

Indeed, undertakings that seem utterly routine to most can require the ADHD entrepreneur to put all of these recommendations into action. Just to pull off a business lunch, for instance, they need the freedom, cooperation, and time literally to put themselves in position to talk productively with a prospective investor or customer. "I can't sit in a restaurant with people on both sides of me," says Suster. "The noise traffic makes it impossible for me to concentrate, because I hear voices from both directions, and I can't pay attention to the people I'm with. I just know I'm not going to survive at that table. So when we get to restaurants, I won't sit down until we pick the right table."

Without sustained management, ADHD can drive those with it in multiple directions, with no regard for intent or results.

And even when all these supports are in place--when someone has all the right people around them and is managing routine tasks on a personalized schedule--there's still no guarantee of success. Why? Because of another often-problematic aspect of ADHD that the author Stephen Covey has called urgency addiction. The ADHD brain requires a skydive to experience the same thrill most people get from a Ferris wheel. So while the best time to accomplish most tasks, for most people, is when they're important but not yet pressing, those with ADHD are often unmotivated to finish them until they're absolutely at their most urgent. Deadlines themselves become the stimulus necessary for action. As Baxter puts it, "Every day could be a cliffhanger."

That can be a dangerous way to operate--and exasperating for fellow employees who are subject to the mania of last-minute scrambles and stresses. But it also breeds striking confidence in the entrepreneurs who pull it off.

Illustration by Matthieu Bourel

ONE DAY IN February, Suster sat at a desk in his home office and flipped through a stack of pages filled with scrawl. "I have 1,200 people coming to L.A. in two weeks," he said with a chuckle. He was preparing for Upfront's annual summit. "This is my presentation--a series of notes that haven't been turned into slides yet. Most of my colleagues wrote theirs three or four weeks ago. This would drive them nuts--they wouldn't be able to sleep at night. But I need to have my back against the wall to get my creative juices flowing."

It was only in 2014 that Suster got formally diagnosed. Ever since, he's talked openly and written often about how he's learned to integrate his business skills with his coping strategies for ADHD. "I don't call it a disorder," he says. "It's how our brains are wired."

Today, Suster will bring a pad to meetings, even to movies, and when he feels himself getting bored, he'll begin taking notes about what he's going to do afterward. He leaves his phone behind, to avoid distraction. He's asked Tania to stop giving him puzzles as gifts so he won't get lost in trying to solve them. He carefully watches what he eats. In the morning, proteins, which stimulate the production of neurotransmitters, help improve his concentration. Sugar and carbs, on the other hand, make him feel like Ping-Pong balls are bouncing inside his head. "If you set yourself up for success," he says, "you're more likely to stay in the moment."

Suster also realizes he often needs to delegate either process management or the completion of tasks to others. "I come up with a million ideas, and I can take abstract things and create boxes around them and kick off initiatives and go really deep," he says. "But entrepreneurship requires you to execute and get things done. So my whole life, I have paired myself with those I call completer/finishers."

Even so, for the ADHD mind, creative breakthroughs still tend to come under intense time pressure. We don't know how much we still have to learn about how divergent brains work. But there's one fact those like Suster, and those close to them, must learn to love, or at least accept: At its best, ADHD is high-risk/high-reward.

"The balance is, I am not going to fail, and I'm not going to be the cause of other people's failure," Suster says as he waves his sheaf of scribbled papers. "I know I'm going to get this done. I have 54 years of proof that I'm going to get it done.

"I just can't get it done early."

Photo Credit: Illustration by Matthieu Bourel.